Featured

Trending

Thoughts

Media

Contest April 2024

Art & Illustration

Beauty & Fashion

Business

Climate & Environment

Comics

Culture

Education

Faith & Spirituality

Finance

Health & Wellness

History

Humor

International

Literature

Miscellaneous

Music

News

Parenting

Philosophy

Politics

Religion

Science

Sports

Technology

thinkspot

Travel

A Guide for Social Justice Paradox - Part 7

more_horiz

Robert "RSnake" Hansen

April 26 2024 at 01:33 am

This topic is a nerve I have an impulse to press lately. Our culture has been working though a social cycle of high-trust peaking, and then this trust being preyed upon and monetized by a kind of rent-seeking behavior, obsession with zero-sum game, and it may well have to do with dynamics of shrinking demographics. As a cohort (not always a population - it could be a race or subculture) declines in numbers - the rates of predatory sociopathy might increase. There has been a lot of talk about sociopathy lately - and (for now at least) I'm not done with either the concept or the experience. It seems none of us are. Michael Knowles was going on about the new "sociopathy awareness" book that came out, written by Patric Gagne. Beyond the usual "pathology grifter" suspicion that is totally warranted about such a book, there are underlying dynamics that people are just barely staring to pay attention to. Gagne herself notes that cases of sociopathy are rising and are undiagnosed. As much as I dislike her general (what I would consider to be enabling) approach, it is apparent via her statistics (and by my own personal observations) that the number is rising. So what is causing this? Surely it is not a case of "born this way." I remember the attitude coming out of the 80s that "some people are just like that" and even recently, what seems to be the mainstream notion is that children of a certain temperament, "not properly socialized" newer develop proper empathy or conscience. I don't think that is the case at all. Children must be born with some great degree of empathy. A child in the womb will hear and to a great degree feel what the mother does. Babies and very young children will laugh when others laugh, cry when others cry. It is the instance of trauma, and specifically unresolved trauma, that really tends to create sociopathy. Ani I don't think I am alone in thinking that the "cluster B" disorders are properly seen on a spectrum with psychopathy on one end tilting into criminal behavior, sociopathy being more circumspect, borderline being more subtle than sociopathy and PTSD being something that we can all at least identify with. All of us are able to understand the kind of numb shock or unmoved anger where we can for a time, feel disconnected from the humanity of someone who is considered an adversary, or a threat. As this spectrum tightens, that "for a time" becomes the "ongoing steady way of life" and the adversary becomes the whole world. But that's not the limit of what we have to deal with. Just as the now-famous example of the one vegetarian family member gets the whole family on tofu, a critical mass of sociopathy can oblige the surrounding individuals to behave in a sociopathic manner. NOW - add to this the fact that drugs (especially cocaine (with what music producer Steve Albini so-directly called "numbing both physical and spiritual") but even marijuana/THC) will induce a kind of trauma as part of the high and crash itself, and we see in the USA, a coming wave of socially corrosive temperament. Are we expected to do anything about this? I hope so. One answer would be to address the trauma. For some reason, I have seen and heard therapist say that there is no cure for Borderline, and certainly no cure for sociopathy. I don't think we should be accommodationist, but there are ways of addressing this trauma. Part or the trouble (as always) is if people won't want to admit to any of it. The zero-sum mindset tends to magnetize itself to people with high amounts of empathy who are also very diligent. Skeptical people who don't work hard make terrible con-marks. Part of the trouble is that the demoralized 3rd world mindset induced by a zero-sum view leads to a dominant signal in the culture of people who are skeptical and don't work hard. High conscientiousness, low agreeability… this is the combination that "spoils the Game" for all those game theorists hoping to get away with whatever machiavellian cluster-b thought they have at the moment. The trick for us would be to decrease agreeability while maintaining or increasing empathy. Late Victorian England is a good example of this. And famously enough, Georgian England and the early Victorian were famous enough for having a fair amount of sociopathic brutality. I think the same contrast can also be recapitulated going from Late Republican Rome where women like the wife or Marc Antony did things like stab the tongue of the deceased Cicero's head with her silver hairpin, just to make a point. We have been through these transitions before. I'd like to think that the spine (or upper lip?) stiffening is already underway. We see it in anything called "based" - the spine-reinforced refusal to be moved my manipulation. SO - we have choppy times ahead - but I am a bit of an optimist. None of this happens automatically. The "little games" need to stop, the stilted pandering and pretending to identity. The rise of social media greatly scaled and amplified the reach of sociopathic action. We find that in cancel culture, yelp reviews, constant-strategy-filled relationships between men and women. But I think an immunity is building - at least it feels that way.

A Guide for Social Justice Paradox - Part 4

more_horiz

Robert "RSnake" Hansen

April 03 2024 at 01:01 pm

When Race Trumps Merit: How the Pursuit of...

more_horiz

Heather Mac Donald

April 03 2024 at 02:59 pm

Disparate Impact Thinking Is Destroying Our...

more_horiz

Heather Mac Donald

April 05 2024 at 09:02 pm

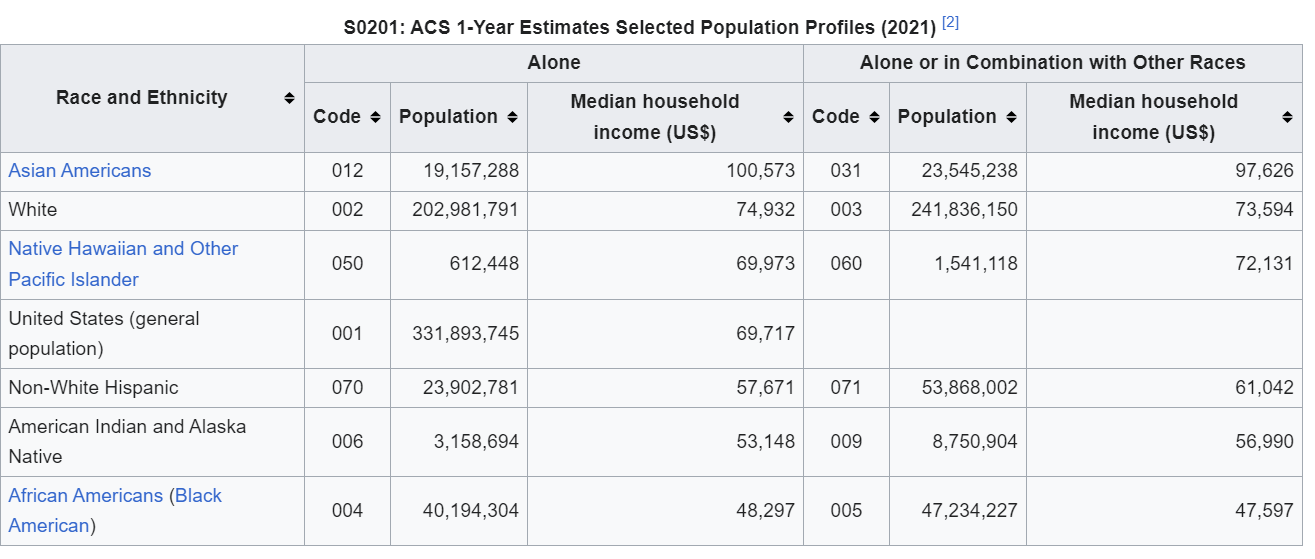

The most consequential falsehood in American public policy today is the idea that any racial disparity in any institution is by definition the result of racial discrimination. If a cancer research lab, for example, does not have 13 percent black oncologists—the black share of the national population—it is by definition a racist lab that discriminates against competitively qualified black oncologists; if an airline company doesn’t have 13 percent black pilots, it is by definition a racist airline company that discriminates against competitively qualified black pilots; and if a prison population contains more than 13 percent black prisoners, our law enforcement system is racist. The claim that racial disparities are proof of racial discrimination has been percolating in academia and the media for a long time. After the George Floyd race riots of 2020, however, it was adopted by America’s most elite institutions, from big law and big business to big finance. Even museums and orchestras took up the cry. Many thought that STEM—the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—would escape the diversity sledgehammer. They were wrong. The American Medical Association today insists that medicine is characterized by white supremacy. Nature magazine declares that science manifests one of “humankind’s worst excesses”: racism. The Smithsonian Institution announces that “emphasis on the scientific method” and an interest in “cause and effect relationships” are part of totalitarian whiteness. As a result of this falsehood, we are eviscerating meritocratic and behavioral standards in accordance with what is known as “disparate impact analysis.” Consider medicine. Step One of the medical licensing exam, taken during or after the second year of medical school, tests medical students’ knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and pathology. On average, black students score lower on the grading curve, making it harder for them to land their preferred residencies. Step One, in other words, has a “disparate impact” on black medical students. The solution, implemented last year, was to eliminate the Step One grading disparity by instituting a pass–fail system. Hospitals choosing residents can no longer distinguish between high and low achieving students—and that is precisely the point! The average Medical College Achievement Test (MCAT) score for black applicants is a standard deviation below the average score of white applicants. Some medical schools have waived the submission of MCAT scores altogether for black applicants. The tests were already redesigned to try to eliminate the disparity. A quarter of the questions now focus on social issues and psychology. The medical school curriculum is being revised to offer more classes in white privilege and focus less on clinical practice. The American Association of Medical Colleges will soon require that medical faculty demonstrate knowledge of “intersectionality”—a theory about the cumulative burdens of discrimination. Heads of medical schools and chairmen of departments like pediatric surgery are being selected on the basis of identity, not knowledge. The federal government is shifting medical research funding from pure science to studies on racial disparities and social justice. Why? Not because of any assessment of scientific need, but simply because black researchers do more racism research and less pure science. The National Institutes of Health has broadened the criteria for receiving neurology grants to include things like childhood welfare receipt because considering scientific accomplishment alone results in a disparate impact. What is at stake in these changes? Future medical progress and, ultimately, lives. Standards are falling in the legal profession, which came up with the disparate impact concept in the first place. Upon taking office in 2021, President Biden announced that he would no longer submit his judicial nominees to the American Bar Association for a preliminary rating. Why? According to a member of the White House Counsel’s Office, allowing the ABA to vet candidates would be incompatible with the “diversification of the judiciary.” This claim was dubious. The ABA, after all, cannot open its collective mouth without issuing a bromide about the need to diversify the bar. Its leading members are obsessed with the demographics of corporate law firms and law school faculties. This is the same ABA that gave its highest rating to a Supreme Court nominee who as a justice would make the false claim during a challenge to Covid vaccine mandates that “over 100,000 children are in serious condition [from Covid] and many are on ventilators.” State bar associations are also busy watering down standards to eliminate disparate impact. In 2020, California lowered the pass score on its bar exam because black applicants were disproportionately failing. Only five percent of black law school graduates passed the California bar on their first try in February 2020, compared to 52 percent of white law school graduates and 42 percent of Asian law school graduates. The lack of proportional representation among California’s attorneys was held to be proof of a discriminatory credentialing system. The pressure to eliminate the Law School Admission Test (LSAT) requirement for law school admissions is growing, because it too has a disparate impact. As a single mother told an ABA panel, “I would hate to give up on my dream of becoming a lawyer just due to not being able to successfully handle this test.” Note the assumption: the problem always lies with the test, never with the test taker. The LSAT requirement will almost certainly be axed. The curious state of our criminal justice system today is a function of the disparate impact principle. If you wonder why police officers are not making certain arrests, or why district attorneys are not prosecuting whole categories of crimes—such as shoplifting, trespassing, or farebeating—it is because apprehending lawbreakers and prosecuting crime have a disparate impact on black criminals. Urban leaders have decided that they would rather not enforce the law at all, no matter how constitutional that enforcement, than put more black criminals in jail. Walgreens, CVS, and Target would rather close down entire stores and deprive their elderly customers of access to their medications than confront shoplifters and hand them over to the law, because doing so would disproportionately yield black shoplifters, as the viral looting videos attest. Macy’s flagship store in New York City was sued several years ago because most of the people its employees stopped for shoplifting were black. The only allowable explanation for that fact was that Macy’s was racist. It was not permissible to argue that Macy’s arrests mirrored the shoplifting population. Even colorblind technology is racist. Speeding and red-light cameras disproportionately identify black drivers as traffic scofflaws. The solution to such disparate impact is the same as we saw with the medical licensing exam: throw out the cameras. The result of this de-prosecution and de-policing has been widespread urban anarchy and, in 2020, the largest one-year spike in homicide in this nation’s history. Thousands more black lives have been lost to drive-by shootings. Dozens of black children have been fatally gunned down in their beds, in their front yards, and in their parents’ cars. No one says their names because their assailants were not police officers or white supremacists. They were other blacks. UNCOMFORTABLE FACTS We need to face up to the truth: the reason for racial underrepresentation across a range of meritocratic fields is the academic skills gap. The reason for racial overrepresentation in the criminal justice system is the crime gap. And let me issue a trigger warning here: I am going to raise uncomfortable facts that many well-intentioned Americans would rather not hear. Keeping such facts off stage may ordinarily be appropriate as a matter of civil etiquette. But it is too late for such forbearance now. If we cannot acknowledge the skills gap and the behavior gap, we are going to continue destroying our civilizational legacy. Let me also make the obvious point that I am talking about group averages. Thousands of individuals within underperforming groups outperform not only their own group average but great numbers of people within other groups as well. Here are the relevant facts. In 2019, 66 percent of all black 12th graders did not possess even partial mastery of basic 12th grade math skills, defined as being able to do arithmetic and to read a graph. Only seven percent of black 12th graders were proficient in 12th grade math, defined as being able to calculate using ratios. The number of black 12th graders who were advanced in math was too small to show up statistically in a national sample. The picture was not much better in reading. Fifty percent of black 12th graders did not possess even partial mastery of basic reading, and only four percent were advanced. According to the ACT, a standardized college admissions test, only three percent of black high school seniors were college ready in 2023. The disparities in other such tests—the SAT, the LSAT, the GRE, and the GMAT—are just as wide. Remember these data when politicians and others vilify Americans as racist on the ground that this or that institution is not proportionally diverse. We can argue about why these disparities exist and how to close them—something that policymakers and philanthropists have been trying to do for decades. But in light of these skills gaps, it is irrational to expect 13 percent black representation on a medical school faculty or among a law firm’s partners under meritocratic standards. At present you can have proportional diversity or you can have meritocracy. You cannot have both. As for the criminal justice system, the bodies speak for themselves. President Biden is fond of intoning that black parents are right to fear that their children will be killed by a police officer or by a white gunslinger every time those children step outside. The mayor of Kansas City proclaimed last year that “existing while black” is another high-risk activity that blacks must engage in. The mayor was partially right: existing while black is far more dangerous than existing while white—but the reason is black crime, not white vigilantes. In the post-George Floyd era, black juveniles are shot at 100 times the rate of white juveniles. Blacks between the ages of ten and 24 are killed in drive by shootings at nearly 25 times the rate of whites in that same age cohort. Dozens of blacks are murdered every day, more than all white and Hispanic homicide victims combined, even though blacks are just 13 percent of the population. The country turns its eyes away. Who is killing these black victims? Not the police, not whites, but other blacks. As for interracial violence, blacks are a greater threat to whites than whites are to blacks. Blacks commit 85 percent of all non-lethal interracial violence between blacks and whites. A black person is 35 times more likely to commit an act of non-lethal violence against a white person than vice versa. Yet the national narrative insists on the opposite idea—and too many dutifully play along. These crime disparities mean that the police cannot restore law and order in neighborhoods where innocent people are most being victimized without having a disparate impact on black criminals. So the political establishment has decided not to restore law and order at all. CIVILIZATION AT STAKE It is urgent that we fight back against disparate impact thinking. As long as racism remains the only allowable explanation for racial disparities, the Left wins, and our civilization will continue to crumble. Even the arts are coming down. Classical music, visual art, theater—all are dismissed as a function of white oppression. The Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted an astonishing show last year called the Fictions of Emancipation. The show’s premise was that if a white artist creates a work intended to show the cruelties of slavery, that artist (in this case, the great 19th century French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux) is in fact arguing that the natural condition of blacks is slavery. Prosecuting this nonsensical argument required the Met to ignore or distort almost every feature of the Western art tradition—including the representation of the nude human body, artists’ use of models, and the sale of art. Only Western art is subjected to this kind of hostile interpretation. Chinese, African, and Indian cultural traditions are still treated with curatorial respect, their works analyzed in accordance with their creators’ intent. As soon as a critic turns his eye or ear on Western art, however, all he can see or hear is imperialism and white privilege. It is a perverse obsession. We are teaching young people to dismiss the greatest creations of humanity. We are stripping them of the capacity to escape their narrow identities and to lose themselves in beauty, sublimity, and wit. No wonder so many Americans are drowning in meaninglessness and despair. We must stop apologizing for Western Civilization. To be sure, slavery and segregation were grotesque violations of America’s founding ideals. For much of our history black Americans suffered injustice and gratuitous cruelty. Today, however, every mainstream institution is twisting itself into knots to hire and promote as many underrepresented minorities as possible. Yet those same institutions grovelingly accuse themselves of racism. The West has liberated the world from universal squalor and disease, thanks to the scientific method and the Western passion for discovery and knowledge. It has given the world plumbing, hot showers in frigid winters, flight, clean water, steel, antibiotics, and just about every structure and every device that we take for granted in our miraculously privileged existence—and I use the word “privilege” here to refer to anyone whose life has been transformed by Western ingenuity—i.e., virtually every human being on the planet. It was in the West that the ideas of constitutional government and civil rights were born. Yes, to our shame, we had slavery. What civilization did not? But only the Anglosphere expended lives and capital to end the nearly universal practice. Britain had to occupy Lagos in 1861 to get its ruler to give up the slave trade. The British Navy used 13 percent of its manpower to blockade slave ships leaving the western coast of Africa in the 19th century, as Nigel Biggar has documented. Every ideal that the Left uses today to bash the West—such as equality or tolerance—originated in the West. *** The ongoing attack on colorblind excellence in the U.S. is putting our scientific edge at risk. China, which cares nothing for identity politics, is throwing everything it has at its most talented students. China ranks number one in international tests of K-12 math, science, and reading skills; the U.S. ranks twenty-fifth. China is racing ahead in nano physics, artificial intelligence, and other critical defense technologies. Chinese teams dominate the International Olympiad in Informatics. Meanwhile the American Mathematical Association declares math to be racist and President Biden puts a soil geologist with no background in physics at the top of the Department of Energy’s science programs. This new science director may know nothing about nuclear weapons and nuclear physics, but she checks off several identity politics boxes and publishes on such topics as “A Critical Feminist Approach to Transforming Workplace Climate.” What do we do in response to such civilizational immolation? We proclaim that standards are not racist and that excellence is not racist. We assert that categories like race, gender, and sexual preference are never qualifications for a job. I know for a fact that being female is not an accomplishment. I am equally sure that being gay or being black are also not accomplishments. Should conservative political candidates campaign against disparate impact thinking and in favor of standards of merit? Of course they should! They will be accused of waging a culture war. But it is the progressive elites, not their conservative opponents, who are engaging in cultural revolution! Most conservatives today are not even playing defense. How about legislation to ban racial preferences in medical training and practice? How about eliminating the disparate impact standard in statutes and regulations? Conservatives should by all means promote the virtues of free markets and limited government, but the diversity regime is the nemesis of both. Lowering standards helps no one since high expectations are the key to achievement. In defense of excellence we must speak the truth, never apologize, and never back down. Originally published at imprimus.hillsdale.edu

Not long after my ninth birthday is when I first began hearing my father violently coughing up blood on a regular basis. Rarely did I hear anymore quiet that lasted longer than a few sparse minutes from the living room where he'd sleep alone in the fold-out bed. It'd been months since I last saw him in actual clothes as he now only wore different sets of the same bland pajamas my mom probably picked out for him in a few different colors. He'd probably never again wear a nice button-up shirt. What a non-issue that must be to a healthier man whose lungs weren't rotting of cancer. They probably wore very nice, really expensive shirts everyday, like my own dad used to do before he got sick. Now, he was on his way out. That much was obvious, even to me. So when one day after school, I opened my bedroom door to find my only aunt who I hadn't seen in years, standing there cheerfully humming to herself while cleaning up my toys for me, I should've put two and two together. She stayed for the next six months. In three my dad would die in his sleep and it'd be her who'd hear the loud gasp in the middle of some random night, not realizing until morning it was actually his last living breath before his body finally gave up fighting. She stayed another three months afterwards to look after her now-widowed sister. I don't remember much from that period of my life. Since I was strategically sent away to live with distant relatives who owned a condo in Queens, it's not like I was around to make many memories anyway. If I try to think back now, it feels like lifetimes ago. All I can tap into is seeing a lot of black clothes and faint whimpering. It feels like the sounds of sobbing were never too far off. It's eerily ambiguous though. Still, the days I was able to spend with my aunt seemed like miracles. Those were the only times during that period where I'd feel truly happy. Like a much-needed return to form for the younger me who laughed constantly as a child. I loved "Mamateta," and even though nobody knows why I gave her that nickname, I used it for years. She adored me and took every opportunity to prove it. Though I left Romania when I was four, I retained many more memories of my aunt than anyone else. How she'd play with me when everyone else was too busy, or how she'd nurse the many cuts and scrapes I'd get on my elbows and knees—, these things must've left quite an impact on my single-child consciousness. I specifically remember an instance where the paper cut on my index finger was so deep that I wanted to burst into tears just looking at it. While cleaning it and putting on a bandaid, I remember my aunt saying, "it feels like there's a tiny little heartbeat inside your finger doesn't it?" I nodded. "I know sweetheart, I've had this happen to me before too." This was her amazing charm. She was easy to talk to. Such a sweet, honest lady. Though she and my mother grew up side by side, they were different people. She took after their own mom, while mine walked in her father’s footprints out of pure admiration. They were sisters nonetheless. So when Mamateta was told that she had a tumor growing within her liver this past year, it was difficult knowing the treatment she'd get wasn't going to be the world's best by any means. As the months passed, her condition worsened and last Monday she fell into a coma. I heard the helplessness in my mother’s voice when she called to tell me. You try your best in these types of situations—, to console your loved ones and make sure they know that you'll be a rock-solid crutch for them during whatever may come. You try to think two steps ahead of whatever's currently happening, just in case. The spur-of- the-moment cross-Atlantic trips have to be every grieving family member's worst nightmare. Just the logistics of it all. And in their mental condition? Of course I was preparing to jump at any request my mom would make. Life does its thing anyway though and so, 24 hours later, her sister—, whose real name is Rodica—, passed away. My family isn't part of the ultra-wealthy in Romania. And because the country's still reeling from decades of deep corruption, the middle class is virtually non-existent. Economists can explain with much more elegance than I'm able to why this is utterly unfortunate for the bottom 99%. If you aren't part of the wealthy, you're part of the poor. And because what you do to one side of the equation, you have to do to the other, they're ultra-poor. It's a sad, sad thing. Either way, my mom begins to explain the finer details of a traditional Romanian mourning process. It's not something I know anything about or ever witnessed in person. After the dearly departed are moved into the living room, they are generally laid down on the center table for viewing. For the next three days, while the men and other experienced woodworkers craft a coffin from scratch, the family serves non-stop coffee and treats to an army of mourners who will randomly pop in and out at all times of the day and night and next day and following night and so on. All this to a constant background flurry of crying, sobbing, sharing stories of precious memories, wails of disbelief, loud prayers, and who knows what else. It's a pure emotional rollercoaster, a dramatic play in so many scenes filled with neighbors from five villages over who you may have never met before, but who've heard the tragic news and wanted to come pay their respects. It's touching but definitely not something an outsider would feel immediately at home around. "And is the body at least covered this entire time?," I ask my mom. "No. For three days, they live alongside it." "Seriously?" "They have no other options. No ambulance comes and takes them away like they do here. Over there, you look after your own dead. And when the coffin is completed, they’ll place her inside and carry it out into the countryside to her burial plot in a procession through town." As selfish as this next feeling was, I didn't want my mom to go. I didn't want her to be apart of it, not these days, not anymore. After so much, I wanted her to just be able to rest, not have to endure something of that magnitude. I can't imagine three hours of nonstop crying let alone three days. Somehow, the Universe seemed to hear my inner-hopes. Our entire family begged her to stay put, to stay home, that there was nothing more she could do. So instead of having to finalize last-minute plans of getting her from one continent to another, she was able to hop on an Amtrak and spend this past week here in Chicago with me. To recharge her batteries I guess. To just be able to find some mental quiet and emotional peace. Now, as I'm close to wrapping up this essay and seeing her off downtown at Union Station for her train back home, I'm sincerely trying to put myself in her shoes. I'm sure losing a sibling you've spent a lifetime growing up with is a weird feeling to have to go through. To outlive them, to think that they could've done a bit more with their life if only they would've had more time. Maybe it makes someone think about their own mortality and where they've gotten in seeing their own personal dreams coming true. Maybe my mom’s running over all of these things in her mind to the point where there's nothing left to think about. Maybe. All I can try and do is my part as her only child, her only flesh and blood, to try and live the best life I can in her name. Time will tell how successful I'll be in doing that, but an even greater feeling though, is when we can think of our loved ones who aren't here with us any longer and not feel a bit of regret. To feel a warmth and be completely calmed by just the mere thought of their name. To feel a deep need to smile because that's what they would've wanted you to do. Like even when you want to just give in to the sadness for a second and purge yourself of tears, your body physically won't let you. A familiar presence fills your immediate space and a gentle touch directly on your heart that makes you involuntarily inhale much deeper than you have in a while. Those are the types of things I hope my mother can feel as she sits down at her window-seat and readies herself for a deep meditative trip into her inner-consciousness for the next seven or so hours. Knowing the peace and tranquility she'll emerge on the other side of this experience with, how can anyone still harbor any doubt that our souls are indeed, things which don't adhere to either the human concept or limitations of "time?" That they transcend realms of possibility. That whenever there's even the smallest hint of real love, not even the giving up of one's own body and leaving it behind for greater vessels can break a bond between two sisters.

The news today is that Iran seized a cargo ship owned by a Jew, and launch drone attacks against Israel. why wouldn’t they? Queers for Palestine run Biden optic, and the White House is a joke. Inclusive includes mentally derelicts and the gender psychotic to the highest policy of the land. American policy is to hold up their bums and say drill here. As if manna from heaven would be any more of a miracle drop than Biden landing his gig as Leader of the Free Workd. This is Alfred E. Newman stuff, a total farce. Biden shoots duds. That is a guarantee. China and Russia are all on board. The time is right. Trump is no slouch, and tomorrow is a different world. BIPOC is all about the revenge against the West. Jordan Peterson often comes up with “why didn’t conservatives do nothing” as such a world came into being. The thing is in a 51 49 world, the useful idiots are the only ones that can really do any thing. consevatives can’t go more conservative, but it is liberals that have lost their collective minds. Bill Maher for example. He sees babies in ovens and nine month old babies stabbed in Australia just like the rest of us. So what? It is a 99 to 1 bet he is Biden 2024. And Iran has been chanting Death to America all the while, Maher voting for the Obama Biden Team that cozies to Iran. Alls conservatives can do, other than go Marjorie Taylor Greene and Alex Jones’s crazy themselves, is to well, get married, have children, do the mom and dad thing and ride out the apocalypse. Negative birth rates, spiralling down, yea, conservatives can blame themselves for that. But nine of that won’t change liberal crazy one iota, and that is where the rot has set in. But liberals are enraptured by the reflections of their own virtuous beauty. Unlike deplorable conservatives, these students of Elaine Paegel refuse to demonize anybody, not even Hamas. But there are economic consequences of America being a joke, for Americans themselves. But liberals are gonna to liberal. Didn’t say boo about the white trash in Britain being turned into cum dumps for Asian predators, celebrate Hamas victory Oct 7, appease Iran, fund terrorism with those pallets of cash. And blame conservatives for the country going to hell in a hand basket.

Trending Topics

Recently Active Rooms

[2, 132224, 148356, 153593, 153914, 1835, 60675, 148910, 2314, 153807, 36134, 154181, 154169, 154149, 154180, 133841, 58659, 154179, 154176, 92022, 154137, 146843, 154147, 154175, 154157, 154173, 49133, 154163, 614, 154091, 154072, 153381, 147825, 33581, 48117, 101422, 47054, 1822, 143287, 112609, 154143, 154152, 154099, 90996, 17088, 154124, 149783, 154074, 153792, 153803, 8305, 150682, 17119, 31713, 154026, 154022, 4583, 154071, 153956, 154021, 132294, 1271]